Going into this course, I didn't have a good idea of what economics of organizations meant but I thought it would be a very interesting course regardless. I did not realize just how much economics there are working within organizations and firms themselves. I mean things like transfer pricing, transaction and overhead costs, relationships between upstream/downstream divisions. So I learned there was a lot more theory and math behind economics of organizations than I realized. There has been so much more research done into this fiend that it amazes me, even culminating in Nobel prizes.

I really liked the unique approach to instruction and teaching - I felt like I was learning the concepts in a way that allowed me to understand them unlike most classes where you're thrown textbooks and told to learn concepts on your own. I think the key was the talking, and the discussion like aspect of the class. Ideas, concepts, theories, flowed more freely between teacher and students, allowing us to process information faster and understand deeper too.

I guess I'm trying to say I really liked this style of instruction. Many classes I've taken it's just the professors talking with no interaction or input from the students.

For the Excel homework, I felt that they were written very well and seldom required more explanation. Just by reading the material in the Excel homework, I felt that I could understand what needed to be done to solve the problems. And I liked that after every question, there was a short explanation behind why the answer was what it was. So to be honest, besides going to class, I didn't have to do a whole lot of preparation because the homework prepared me as I was doing it. Generally I had to set aside maybe an hour (although there were a couple times it took longer) to do the homework. For the blogging, it was about the same in terms of how much time I set aside, usually an hour. But in terms of preparation, I read the prompts and think about them for a short while to organize my thoughts before getting to work and writing. I approach all writing that I have to do in a similar way.

I'm not sure what other things I would have liked to see in this course because I don't have much experience or knowledge on economics of organizations (well, I know more now but still). I guess the one thing I would say is maybe if we had done like a case study, or had like a real world example of how economics of organization affected companies like Coca-Cola or nonprofits or something like that. Something more applied and hands on, tangible, so yes some sort of project or case study pertaining to a real world example.

Saturday, December 7, 2013

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

The Relationship between Brand and Reputation

I used to intern at Merrill Lynch for the first two summers of my college life. Now, before the recession, Merrill Lynch was an immense investment banking firm on par with peers like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. But Merrill Lynch, in its competition with them, overextended into mortgage backed securities and other such dangerous derivatives. And since it had done so, it was hit hard by the financial crisis of 2007-08. The same crisis that forced Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers out of business was the one to bring the esteemed and storied Merrill Lynch down to its knees. In the end, in the middle of September of 2008, Merrill Lynch was forced to stomach and accept a takeover offer of $50 billion from lender Bank of America. Bank of America was on the hunt for good deals during the meltdown and bought Countrywide Financial first. When it heard of Merrill Lynch's troubles, the deal was almost too good to pass up. What Bank of America was looking for was the hefty fees and profits provided by Merrill Lynch's brokerage house - in essence Merrill Lynch became nothing more than Bank of America's "wealth management" arm. After the buyout was completed, Bank of America pared or wound down Merrill Lynch's more riskier ventures, the same ventures that defined it as a market leader for generations (like Merrill Lynch Europe or certain aspects of Merrill Lynch investment banking) and directed ML to concentrate its efforts on expanding the domestic brokerage firm. Because of the steady cash and profits provided by Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, it has largely boosted Bank of America's bottom line while BofA has had to deal with losses stemming from subprime mortgages and legal issues.

That is just the back story. There were consequences of Merrill Lynch's overreaching of course, some of them being Merrill Lynch brokers, a lot of the high powered and influential ones, deciding that Merrill Lynch was another glob in a corporate behemoth. Before the merger, brokers had immense power within the firm, indeed, the firm's management catered to them. Now that BofA's corporate management came and sent out financial targets and goals all over the place, essentially telling the brokers what to do, these same brokers wanted nothing more to do with the firm. The financial advisers left in the wake of the merger for other wealth management firms such as Morgan Stanley and UBS (who answered to no higher power). The same can be said of the clients, but to a lesser degree - reports of overall client dissatisfaction quickly grew after the merger and the company had to work around the clock to assauge their clients that nothing would change. But of course, changes did happen.

Before the crisis, Merrill Lynch had a huge brand name and important reputation. These days, rivals and peers look at it as if it has been relegated to the minor leagues once it became acquired. To some degree, I have read that some brokers still with the firm feel that way. They want to compete with the likes of Goldman Sachs, but feel Bank of America stifles them, according to news reports. As a result, and unintended consequence, many people feel less inclined to work for Merrill Lynch, and the brightest minds insist on working at GS or hedge funds.

This just shows how brand name and reputation are intertwined. I spoke about Merrill Lynch but Apple is another prime example of how this works. In several reports and studies, Apple has repeatedly come out on top as the single most valuable corporate brand in the world (I think the value of the brand name itself approached $50 billion). Apple has staked its reputation in the power of its brand and its ability to attract and draw consumers in like moths to a flame. Year after year, it has done it again and again, beating sales estimates of its iPhones and iPads, and in turn, of its Macbooks as well. Without its brand name, Apple couldn't price its products as high as it does. Thus, we can see that the relationship between brand name and reputation is deeply intertwined. Corporations have no choice but to see that their brand and reputation are pristine and valued as highly as possible. That's why they go to great lengths to settle legal issues and court cases before it gets out of hand and public opinion turns negative.

That is just the back story. There were consequences of Merrill Lynch's overreaching of course, some of them being Merrill Lynch brokers, a lot of the high powered and influential ones, deciding that Merrill Lynch was another glob in a corporate behemoth. Before the merger, brokers had immense power within the firm, indeed, the firm's management catered to them. Now that BofA's corporate management came and sent out financial targets and goals all over the place, essentially telling the brokers what to do, these same brokers wanted nothing more to do with the firm. The financial advisers left in the wake of the merger for other wealth management firms such as Morgan Stanley and UBS (who answered to no higher power). The same can be said of the clients, but to a lesser degree - reports of overall client dissatisfaction quickly grew after the merger and the company had to work around the clock to assauge their clients that nothing would change. But of course, changes did happen.

Before the crisis, Merrill Lynch had a huge brand name and important reputation. These days, rivals and peers look at it as if it has been relegated to the minor leagues once it became acquired. To some degree, I have read that some brokers still with the firm feel that way. They want to compete with the likes of Goldman Sachs, but feel Bank of America stifles them, according to news reports. As a result, and unintended consequence, many people feel less inclined to work for Merrill Lynch, and the brightest minds insist on working at GS or hedge funds.

This just shows how brand name and reputation are intertwined. I spoke about Merrill Lynch but Apple is another prime example of how this works. In several reports and studies, Apple has repeatedly come out on top as the single most valuable corporate brand in the world (I think the value of the brand name itself approached $50 billion). Apple has staked its reputation in the power of its brand and its ability to attract and draw consumers in like moths to a flame. Year after year, it has done it again and again, beating sales estimates of its iPhones and iPads, and in turn, of its Macbooks as well. Without its brand name, Apple couldn't price its products as high as it does. Thus, we can see that the relationship between brand name and reputation is deeply intertwined. Corporations have no choice but to see that their brand and reputation are pristine and valued as highly as possible. That's why they go to great lengths to settle legal issues and court cases before it gets out of hand and public opinion turns negative.

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Personal Reputations

I think everyone leaves their personal impact on family, friends, and the workplace. Those are exactly the three places where individuals have the most influence on other people. For almost everyone, their reputations with their families develop as they grow up - with the result being most families know their children extremely well. The same can't exactly be said of friends, i.e. people accumulate friends over time and sometimes, friends aren't always the same (the circle of friends changes). But even so, there are always the few friends that the individual will have known for a long while so there's reputation building between him and them. The same goes for the workplace, an individual builds up reputation and rapport between himself and his colleagues. A reputation is very dependent on how long a person stays or is fixed at a location. This is because that's the best way for people to get to know that individual. But a positive reputation is different - that depends on the individual's personality. So a reputation is one thing - a positive or negative one is something different.

For me, I think I have a strong reputation with my friends. I hang out with a lot of the same people I met during the first month of my freshman year so we have all known each other a long time. Through three and a half years of college, through everything, we still talk and meet up quite often. So not only do my friends know me very well, but I also know them very well. I like to think I have maintained a good and positive reputation amongst my friends. To that end, I can influence behavior if I chose to but I generally opt to form a consensus. The biggest and best example of this is during weekends when we decide to meet up and go to dinner. From past experience, I know it always takes a long time to find a place where we all would like to eat. Therefore, if I were to just say, "Guys, let's just go eat here" and I was adamant about it then we would all go. But I would rather have everyone have enjoy where they are eating rather than one person just choosing to go ahead and making a choice himself. At minimum, that also puts my reputation on the line if everyone didn't enjoy the food or something happened at the restaurant.

I don't consciously think about keeping my reputation intact or enhancing it exactly. I mean that just depends on how good of a friend you are and that's what I try to focus on. If one of my friends needs my help, I try to do my best to help them. Actually, a lot of my friends do come to me for advice, but I always wonder why. It may not necessarily be because I give good advice, but because I've known my friends for a while and they know me. So to answer the question, I guess I would just try to be a good person and a good friend, stay faithful to my character as a dependable individual. The restaurant example was one instance where I could have, if I wished, cashed in my reputation for an immediate gain. It would save time, but it's not who I am. That result also extends to other areas of my life - I wouldn't stake my reputation or cash it in for immediate gain. Although that might be a little different with my parents, i.e. sometimes I played the reputation card. But now that I've grown, I don't do that with anyone.

For me, I think I have a strong reputation with my friends. I hang out with a lot of the same people I met during the first month of my freshman year so we have all known each other a long time. Through three and a half years of college, through everything, we still talk and meet up quite often. So not only do my friends know me very well, but I also know them very well. I like to think I have maintained a good and positive reputation amongst my friends. To that end, I can influence behavior if I chose to but I generally opt to form a consensus. The biggest and best example of this is during weekends when we decide to meet up and go to dinner. From past experience, I know it always takes a long time to find a place where we all would like to eat. Therefore, if I were to just say, "Guys, let's just go eat here" and I was adamant about it then we would all go. But I would rather have everyone have enjoy where they are eating rather than one person just choosing to go ahead and making a choice himself. At minimum, that also puts my reputation on the line if everyone didn't enjoy the food or something happened at the restaurant.

I don't consciously think about keeping my reputation intact or enhancing it exactly. I mean that just depends on how good of a friend you are and that's what I try to focus on. If one of my friends needs my help, I try to do my best to help them. Actually, a lot of my friends do come to me for advice, but I always wonder why. It may not necessarily be because I give good advice, but because I've known my friends for a while and they know me. So to answer the question, I guess I would just try to be a good person and a good friend, stay faithful to my character as a dependable individual. The restaurant example was one instance where I could have, if I wished, cashed in my reputation for an immediate gain. It would save time, but it's not who I am. That result also extends to other areas of my life - I wouldn't stake my reputation or cash it in for immediate gain. Although that might be a little different with my parents, i.e. sometimes I played the reputation card. But now that I've grown, I don't do that with anyone.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Tri-lateral Principal-Agent Model

I think one situation where this arises for a lot of people is their parents, or family. For me, growing

up, my parents were usually on the same page as everything. They would almost always agree on a

variety of going ons in my life, including academics and extracurriculars. But one instance where

they didn't agree was a choice between playing the violin or playing soccer. When I was a kid, I

picked up both, starting the violin and continuing for several years, and likewise with soccer. As I

grew older, it quickly became apparent that I could not hope to do both. Academics were the priority

and the workload grew considerably heavier in high school when I took many AP classes. At first we

decided on a compromise: we decided that I would play both until to the point where the time

consumption of both grew unbearable. At that point, I would decide which extracurricular to keep. In

reality, I suppose the decision all came down to me. Choosing one over the other would certainly

disappoint one of my parents but of course it was up to me and which one I thought I was better at.

It was a hard decision but in the end, I chose soccer over violin. This was just one tame example of

differences in views and one agent stuck in between two different parties.

But like I said earlier, a lot of these differences can arise for people with parents or parents and other

family members. One common example is who a guy or girl will marry - one parent might approve,

the other might disapprove. Or some family members will approve and most won't approve. A lot of

times, the agent will fail someone (i.e. the old adage, you can't make everyone happy), but a few

times it is possible for the agent to satisfy both parties. At least these examples are relatively mild in

comparison to when agents have to make a choice between family and country or love and country.

up, my parents were usually on the same page as everything. They would almost always agree on a

variety of going ons in my life, including academics and extracurriculars. But one instance where

they didn't agree was a choice between playing the violin or playing soccer. When I was a kid, I

picked up both, starting the violin and continuing for several years, and likewise with soccer. As I

grew older, it quickly became apparent that I could not hope to do both. Academics were the priority

and the workload grew considerably heavier in high school when I took many AP classes. At first we

decided on a compromise: we decided that I would play both until to the point where the time

consumption of both grew unbearable. At that point, I would decide which extracurricular to keep. In

reality, I suppose the decision all came down to me. Choosing one over the other would certainly

disappoint one of my parents but of course it was up to me and which one I thought I was better at.

It was a hard decision but in the end, I chose soccer over violin. This was just one tame example of

differences in views and one agent stuck in between two different parties.

But like I said earlier, a lot of these differences can arise for people with parents or parents and other

family members. One common example is who a guy or girl will marry - one parent might approve,

the other might disapprove. Or some family members will approve and most won't approve. A lot of

times, the agent will fail someone (i.e. the old adage, you can't make everyone happy), but a few

times it is possible for the agent to satisfy both parties. At least these examples are relatively mild in

comparison to when agents have to make a choice between family and country or love and country.

Friday, October 18, 2013

How Did We Lose the Share-the-Spoils Mentality?

Note: This is part two of the homework assignment - but this only addresses the larger issue of why we lost the share-the-spoils mentality.This part goes off on a tangent that tries to answer how we have lost that mentality that was so prevalent before. Part one is the blog post underneath that addresses the prompt directly. Both parts share the same introduction.

In the article presented by Jonathan Haidt, “How to Get Rich to Share the Marbles”, the University of Virginia professor talks about a so called “share-the-spoils” mentality that exists among humans. According to studies conducted by researchers at the Max Planck institute in Germany, this mentality does not exist with our closest cousins, the chimpanzees. It developed for us thousands of years ago when humans started foraging and hunting together for food. Unfortunately, this mentality resides within us as a switch that is not permanently on. The positive feelings of community and together-ness generated by this mentality are expressed, i.e. the switch is turned on, when everyone collaborates and cooperates together for the greater good. As the author pointed out, throughout history we have been asked to come together, for a higher calling than just working for ourselves. This pertains to not only presidents like Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy but other leaders, like Martin Luther King and Churchill, as well. They presented compelling cases why, through cooperation and unity, we could overcome adversity and achieve grand projects and goals. Such things that could only be dreamed about became reality.

In the article presented by Jonathan Haidt, “How to Get Rich to Share the Marbles”, the University of Virginia professor talks about a so called “share-the-spoils” mentality that exists among humans. According to studies conducted by researchers at the Max Planck institute in Germany, this mentality does not exist with our closest cousins, the chimpanzees. It developed for us thousands of years ago when humans started foraging and hunting together for food. Unfortunately, this mentality resides within us as a switch that is not permanently on. The positive feelings of community and together-ness generated by this mentality are expressed, i.e. the switch is turned on, when everyone collaborates and cooperates together for the greater good. As the author pointed out, throughout history we have been asked to come together, for a higher calling than just working for ourselves. This pertains to not only presidents like Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy but other leaders, like Martin Luther King and Churchill, as well. They presented compelling cases why, through cooperation and unity, we could overcome adversity and achieve grand projects and goals. Such things that could only be dreamed about became reality.

But at the same time, I see why this has all but disappeared.

President Lincoln dealt with a devastating and fractious civil war; in the

twentieth century, there were two world wars and the looming specter of communism

and the bastion of nefariousness that was the USSR. But in the twenty-first

century, there are no tangible, huge threats – in the form of war or a country,

or otherwise. As the world’s sole superpower, the United States does not have

real rivals (yet), economically or militarily. This will eventually change as

other countries, notably China, are fast catching up. But in the meanwhile,

there is no one or no challenge (yet) to the United States so as a people we do

not perceive any threats. And it has been this way since the 1980s with the Reagan

presidency, when it was clear that we had an edge in our cold war race/battle

with the Soviet Union. Towards the end of the 80s, by vastly outspending the

USSR and with Reagan being the first president to turn the United States from a

creditor to a debtor nation since World War I, it was clear we would eventually

win. After that, there has not been a single threat or grand project to bring

the nation together, with the exception of 9/11. In the aftermath of 9/11, we quickly

came together as a nation but over time, that display of unity has dissipated.

So now we are left at square one again and we have no grand ambition, like the

moon landing, or grand perceived evil, like the Soviet Union, to bring us

together.

President Obama has been on the right track to tie everything

back to a sense of community and shared prosperity. But that mentality that

endured throughout both world wars and up until the 80s has lay dormant among

us. And that is primarily because of the new mentality of “pull yourself by

your own bootstraps” and “become successful with hard work and individual

effort”. Incidentally, this mentality took over around the same time as the

80s, when capitalism and corporate America swiftly rose through deregulation,

and when inequality started increasing. Now I have no problem with this

mentality, in fact, I applaud it and I find it a testament to the American

character. But at the same time, I do not see why this and the “shared

prosperity” or “share-the-spoils” mentality cannot actively coexist at the same

time. It’s completely fine to work hard by yourself and earn success by your

individual efforts, but there is no problem with extending a hand out to your

neighbor if you think he needs help (with no perceivable gain for you) or with

asking for help from your neighbor. That’s what has been lost over the past few

decades – this sense of “we’re part of the same community” and “let’s build

this nation together”. These days, for politicians, if a law does not do

anything for their district or state, it’s useless to them. But what about the

people that live in other districts or states? Are they not Americans as well? Do

you have no obligation to them just because you don’t represent them? I ask

because in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, many Republicans denied hurricane

relief to people and businesses on the east coast, namely, New York and New

Jersey. Their reasoning was it increased the debt (I won’t even begin to get

into how wrong that reasoning is). But beyond that, it was the first time this

had happened in Congress – relief and aid bills the aftermath of natural disasters

always rapidly passed Congress with an overwhelming majority of both parties.

All of this long-windedness brings me to one crucial point.

We must find what it is that can tie and hold us together for the greater good –

for a greater purpose than just ourselves or just our neighborhood. It won’t be

as clear or as perceivable as a world war, the moon landing, or the Soviet

Union. But we must find it fast, before we go into a period of relative decline like what happened with the United Kingdom in the 20th century and well, I won’t get into further doom and gloom

stuff. Honestly, it will be incredibly hard but it is possible.

Sharing the Marbles and the Rewards in Team Production

Note: This homework assignment has been split into two parts. Part one answers the actual prompt and the second part addresses the larger issue of sharing the spoils and why we have lost that mentality. This is part one (the actual assignment I suppose).

In the article presented by Jonathan Haidt, “How to Get Rich

to Share the Marbles”, the University of Virginia professor talks about a so

called “share-the-spoils” mentality that exists among humans. According to

studies conducted by researchers at the Max Planck institute in Germany, this

mentality does not exist with our closest cousins, the chimpanzees. It developed

for us thousands of years ago when humans started foraging and hunting together

for food. Unfortunately, this mentality resides within us as a switch that is

not permanently on. The positive feelings of community and together-ness

generated by this mentality are expressed, i.e. the switch is turned on, when

everyone collaborates and cooperates together for the greater good. As the

author pointed out, throughout history we have been asked to come together, for

a higher calling than just working for ourselves. This pertains to not only presidents

like Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy but other leaders, like Martin Luther King

and Churchill, as well. They presented compelling cases why, through

cooperation and unity, we could overcome adversity and achieve grand projects

and goals. Such things that could only be dreamed about became reality. Then,

the reward could be equally felt and shared among all involved. Teamwork is

always rewarded, whether it is a team sport, or a huge project or research program.

There are some tasks that are too big for any one individual to take on alone.

In that scenario, it is always better to form a team to tackle it. Not only

does it make the process faster, but more enjoyable and easier to handle.

I have always felt that doing certain tasks as a team, such

as large finance, statistics or programming assignments, are better and more

efficient for the people involved. For two of my classes, CS 105 and Fin 221,

we had group Excel projects that we had to finish. I honestly felt we

accomplished so much more by working together. I don’t mean just the project

itself, but I mean the learning process and completing it in a timely,

efficient manner. In the same vein, I played soccer throughout middle school

and high school and the sport instilled in me a sense of cooperation, teamwork,

and working hard, but playing by the rules, results in a big rewards and

payoff. Working together means you don’t have to share the burden and you get

to interact with others, and those very human feelings are important for the

real world. So these experiences extend and translate to the real world,

especially with jobs and working in an office. Some of the biggest inventions

and products, like the iPhone, facebook, or Windows, were possible because they

were not an individual task – they were collaborations between groups of people

among divisions in a company. For an example of this, I refer you to a recent

New York Times Magazine piece about Steve Jobs, Apple, and the creation of the

iPhone: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/magazine/and-then-steve-said-let-there-be-an-iphone.html

Imagine

that, without the incredibly hard efforts of Apple employees, we would have

never had a smartphone revolution – or at least, it would not have come as fast

as it did. So yes, the conclusions in

the given New York Times article piece certainly do jive with my experiences

and what I have read so far.

Friday, October 4, 2013

Return to Transfer Pricing and the Utilization of Illinibucks

Specifically, “Illinibucks” could be used for

many things which attain large lines, such as those at bookstores at the

beginning of each semester, or at dining halls at peak hour. Illinibucks could

also be used for registering earlier for campus recreation and activities, or

to book certain venues and spaces (for campus organizations for example), or

even for concerts and guest speaker events. Anything that would require signing

up earlier or accrues a long waiting list of people to join would quality in

this case scenario. I would prioritize my list of activities or events that

have large lines and number them from most to least important. That is where I

would spend my Illinibucks; suppose I love food (well, I do, but who doesn’t) –

then I would prioritize dining hall lines on the days my favorite lunch/dinner

is served or on days I have exams and don’t have time to wait in line. I might

also utilize them for sporting events or concerts that include my favorite

artists. I guess I am saying I would spend these Illinibucks, or credits, on

things, events, or instances that give me the most utility. To that end, I

would not spend them willy nilly, but save up until I needed them and then spend

it.

As with any sort of price transaction with buyers

and sellers, this would eventually result in a “Illinibucks” market. If people

could buy and sell Illinibucks, then that would definitely occur. Following

that will be “innovations” and newfangled creations arising in this marketplace

that will include options and derivatives and futures that may or may not be

harmful to its investors. Okay, it might not go that far, but there will be a

new market where people who really want these Illinibucks will want to buy them

and people who have an infinite amount of patience and see no use for

Illinibucks will sell them. Of course this is assuming people can buy and sell

Illinibucks. So in this case, if the administered price was too low, too many

people would be cutting ahead to the front of lines and there would really be

no improvement in cutting waiting time since there are more people than

expected. If the administered price was too high, not enough people would be

using them often enough to justify having them and on the Illinibucks

themselves on having any sort of impact on the student body at large.

Friday, September 27, 2013

Managing Future Income Risk

Going into college, I did not think about minimizing my own future

income risk because, let’s face it, I was young. But my parents, on the other

hand, definitely had that on their minds: they completely covered the cost of

my college education so that I would be debt free upon graduation. Given that

I’m an out-of-state student, that is no small cost. With the same thoughts

toward my future, my parents suggested I major in electrical engineering, where

the technical skills and know-how I would learn would make it very easy to find

good employment. Even though I had my reservations, I agreed, knowing that they

were right (as usual). I was semi-interested in technology to begin with so I

thought electrical engineering might work out for me. But even though I was a

fine student, my interest waned as I had to trudge through the basic courses where it’s

rote learning and memorization. Even though we had labs, they weren’t very

hands on, or interesting to be frank. So I decided to switch into economics,

where I have greater passion for my studies and academics. Previously, I’ve

interned at a large financial corporation with the hopes of possibly working

there in the future. I’ve also founded and led the Illini Investment Group as

an extracurricular activity. I’ve done these activities all with the hopes of

them correlating directly into the job market or, alternatively, graduate

school. I know that a career in economics, either through employment or

graduate school will offer me two good paths toward decreasing and better

managing future income risk. In a similar vein, even though I do not have an

older sibling, my older cousin is in medical school and he does have an

interest in medicine, yes, but it was also done with an eye towards a

successful career and decreasing future income risk.

Sunday, September 15, 2013

My Experience with Organizations and Transaction Costs

I'm the president of an organization on campus called the Illini Investment Group. Every Wednesday, when we meet we talk about the financial markets, business news, and facets of the financial world, like stocks and bonds to options and derivatives. I founded IIG in the Spring of 2011 and we were operational the fall of the following semester. Founding an organization and trying to lead it is an immense responsibility and task. The first order of business was to find partners, or an "executive board", not in the least because the university required it for my organization to exist in the first place.

Since I started my organization so early, there haven't been any leadership changes per se. I have remained on board as President and the two other people who I recruited as Treasurer and Tech Chair/Webmaster have also stayed on since the beginning. We have only made additions to our team, adding a Vice President as well as a board member specializing in Economics and its theory applied to real world finance. So we went through some changes in terms of adding members to the exec board, but we also went through other changes. In the beginning, the first year we were active, we didn't have any fees or dues. We wanted it to be a free, open club so that our members could completely enjoy it without incurring any costs. We quickly realized, however, that our options for social activities, like movie & pizza nights or game nights, outside our meetings every week were limited if we did not have some income to spend on extracurricular outings. Even the SORF office can only provide so much funding, especially if we wanted to do something like a trip to Chicago for a day. I used to be against dues because I thought paying was unnecessary but after spearheading this organization, my views have changed. Every enterprise has some sort of expenses and even though us exec members aren't paid, we still need some funds for the payment of equipment or bowling/billiards, and other activities in that vein.

I have also had experience interning at a large financial company for a couple summers. It is a historic and venerable firm, but it is also a very complicated organization that requires thousands working in management. As one can imagine, it is also steeped in bureaucracy (through no fault of its own). A start up or new company is quick, nimble, and agile, able to respond to market changes easily and is groundbreaking or industry-shifting in some way, especially technology companies. But as time goes on, and the company hires more and more personnel, layers of bureaucracy and "management" that weren't there before suddenly appear and take up time, money, and other resources. This phenomenon can be seen across industries where phrases like "corporate behemoth" to describe Microsoft, Exxon, Walmart are regularly used. (As a side note, at least none of these companies are as bad as the U.S. government in terms of bureaucracy.) Maybe some companies can survive this, but adding layers of bureaucracy and becoming a huge organization is a double-edged sword, especially for tech companies: it is a testament to their success but could also lead to their downfall as younger, savvier start ups create products, services, processes or technologies that disrupt and displace established ones.

I point all this out because I feel like organizational structures inherently lend themselves to transaction costs through bureaucracy and red tape - any (economic) inefficiency is a transaction cost. Time, money, and resources are being used up in ways they shouldn't be but seeing as human beings make up these organizations, that is only to be expected. Perhaps the best way to deal with this is to just simply minimize bureaucracy, red tape, and any other inefficiencies as much as humanly possible. If left unchecked, these inherent transaction costs can be dangerous.

Since I started my organization so early, there haven't been any leadership changes per se. I have remained on board as President and the two other people who I recruited as Treasurer and Tech Chair/Webmaster have also stayed on since the beginning. We have only made additions to our team, adding a Vice President as well as a board member specializing in Economics and its theory applied to real world finance. So we went through some changes in terms of adding members to the exec board, but we also went through other changes. In the beginning, the first year we were active, we didn't have any fees or dues. We wanted it to be a free, open club so that our members could completely enjoy it without incurring any costs. We quickly realized, however, that our options for social activities, like movie & pizza nights or game nights, outside our meetings every week were limited if we did not have some income to spend on extracurricular outings. Even the SORF office can only provide so much funding, especially if we wanted to do something like a trip to Chicago for a day. I used to be against dues because I thought paying was unnecessary but after spearheading this organization, my views have changed. Every enterprise has some sort of expenses and even though us exec members aren't paid, we still need some funds for the payment of equipment or bowling/billiards, and other activities in that vein.

I have also had experience interning at a large financial company for a couple summers. It is a historic and venerable firm, but it is also a very complicated organization that requires thousands working in management. As one can imagine, it is also steeped in bureaucracy (through no fault of its own). A start up or new company is quick, nimble, and agile, able to respond to market changes easily and is groundbreaking or industry-shifting in some way, especially technology companies. But as time goes on, and the company hires more and more personnel, layers of bureaucracy and "management" that weren't there before suddenly appear and take up time, money, and other resources. This phenomenon can be seen across industries where phrases like "corporate behemoth" to describe Microsoft, Exxon, Walmart are regularly used. (As a side note, at least none of these companies are as bad as the U.S. government in terms of bureaucracy.) Maybe some companies can survive this, but adding layers of bureaucracy and becoming a huge organization is a double-edged sword, especially for tech companies: it is a testament to their success but could also lead to their downfall as younger, savvier start ups create products, services, processes or technologies that disrupt and displace established ones.

I point all this out because I feel like organizational structures inherently lend themselves to transaction costs through bureaucracy and red tape - any (economic) inefficiency is a transaction cost. Time, money, and resources are being used up in ways they shouldn't be but seeing as human beings make up these organizations, that is only to be expected. Perhaps the best way to deal with this is to just simply minimize bureaucracy, red tape, and any other inefficiencies as much as humanly possible. If left unchecked, these inherent transaction costs can be dangerous.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

The Fine Line Between Academic Integrity and Opportunism

In terms of college, I think the biggest opportunism factor is that in homework and exams. College students regularly find creative ways to circumvent the ideal homework process as perceived by the instructor: each individual diligently does his (or her) homework assignment by himself without any outside help (unless it's a group assignment), all the while learning the concepts and theories taught in class and valuable life lessons in time management - that hard work is its own reward. While all of that is true and would be the best case scenario for both the student and the professor, in reality, students often engage in these creative ways to bypass that whole arduous and time-consuming process.

Students might often collaboratively work in groups when the assignment does not call for it, and while they may not always copy each other's work word for word, it is still not strictly ethical behavior. But what is ethically worse for administrators and professors is how homework solution manuals are passed around by thousands of students to their peers for numerous classes. Most of these classes are introductory classes that form the foundations of what these students will learn later so copying homework solutions really doesn't lead to learning and understanding. In the same vein, having and studying from past exams and (past) exam solutions are ethically questionable as well, especially when it's not the instructor that hands those out to students.

That's not to say these kids are bad students or don't work hard. On the contrary, many students regularly get A's in their exams and classes overall. But with students taking hard classes and more hours after that filled with multiple extracurricular activities, they rarely have the time to go through an ideal homework process. But is that chance to expedite the homework or studying process is opportunistic? Absolutely. Is it dishonest or unethical? That remains to be seen and depends on a variety of other factors, such as circumstances. It's best to examine these on a case-by-case basis. This all circulates back to the gray area between academic honesty and dishonesty - what constitutes academic integrity?

But I say all this because I want to address the point of this blog: I had a friend in high school who absolutely did not consult any solution manuals to any homework assignment and who always studied by herself to get A's on her own merit and hard work. If any of her friends or peers asked her for help, she would always be more than happy to help them conceptually but never gave them straight answers or her homework to copy. All throughout high school, I observed this fact, that even though she presumably could have used other resources, even the perfectly ethical 'office hours' after school with our teachers. As to why she never consulted outside help, I can only speculate that she was very confident in her abilities and knew it was far better to spend time to grasp concepts and do her own work. It was commendable on her part and it paid off extremely well for her - she was class valedictorian and now attends Princeton University.

I know she isn't the only person like that but she's the one that I knew. This example of opportunism is not, say, as bad as a TV drama where the vice president has the antidote to an ailment a first-term president is suffering from but does not give it to him because he wants to be the new president. I wish I had a better story to tell, something with more oomph or pizzazz but the more I think about it, the more I think that this story is appropriate because of the indelible impression it left on my mind. That hard work without looking for shortcuts pays off in the long run. There is a trade-off of the time and effort spent in the short-run but then again, long run is what matters.

Students might often collaboratively work in groups when the assignment does not call for it, and while they may not always copy each other's work word for word, it is still not strictly ethical behavior. But what is ethically worse for administrators and professors is how homework solution manuals are passed around by thousands of students to their peers for numerous classes. Most of these classes are introductory classes that form the foundations of what these students will learn later so copying homework solutions really doesn't lead to learning and understanding. In the same vein, having and studying from past exams and (past) exam solutions are ethically questionable as well, especially when it's not the instructor that hands those out to students.

That's not to say these kids are bad students or don't work hard. On the contrary, many students regularly get A's in their exams and classes overall. But with students taking hard classes and more hours after that filled with multiple extracurricular activities, they rarely have the time to go through an ideal homework process. But is that chance to expedite the homework or studying process is opportunistic? Absolutely. Is it dishonest or unethical? That remains to be seen and depends on a variety of other factors, such as circumstances. It's best to examine these on a case-by-case basis. This all circulates back to the gray area between academic honesty and dishonesty - what constitutes academic integrity?

But I say all this because I want to address the point of this blog: I had a friend in high school who absolutely did not consult any solution manuals to any homework assignment and who always studied by herself to get A's on her own merit and hard work. If any of her friends or peers asked her for help, she would always be more than happy to help them conceptually but never gave them straight answers or her homework to copy. All throughout high school, I observed this fact, that even though she presumably could have used other resources, even the perfectly ethical 'office hours' after school with our teachers. As to why she never consulted outside help, I can only speculate that she was very confident in her abilities and knew it was far better to spend time to grasp concepts and do her own work. It was commendable on her part and it paid off extremely well for her - she was class valedictorian and now attends Princeton University.

I know she isn't the only person like that but she's the one that I knew. This example of opportunism is not, say, as bad as a TV drama where the vice president has the antidote to an ailment a first-term president is suffering from but does not give it to him because he wants to be the new president. I wish I had a better story to tell, something with more oomph or pizzazz but the more I think about it, the more I think that this story is appropriate because of the indelible impression it left on my mind. That hard work without looking for shortcuts pays off in the long run. There is a trade-off of the time and effort spent in the short-run but then again, long run is what matters.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Ronald Coase - One of the Greatest Economists

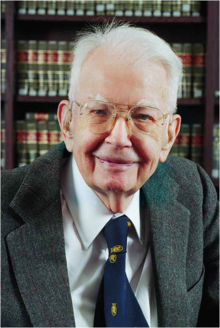

Ronald Coase

Ronald Coase was a British-born American economist who won the 1991 Nobel Prize in Economics for his significant work in transactions costs and property rights in the functioning of the economy (Coase Institute). Born on December 29, 1910, Mr. Coase attended the University of London and the London School of Economics, where he got his Bachelor's degree. He worked at LSE for fifteen years before moving to the University of Buffalo in the mid-1950s. After a brief stint at the University of Virginia from 1958 to 1964, he moved to the University of Chicago, where he was the Clifton R. Musser Professor Emeritus of Economics, and stayed as a distinguished faculty member for the rest of his academic career.

Mr. Coase's work was influential for many reasons but he is especially known for these two: transactions costs of the firm, and how property rights could overcome externalities. The first, he published when he was only 26 years old, in a paper titled "The Nature of the Firm" (1937). In this seminal piece, Mr. Coase tries to explain why people choose to organize themselves into business firms rather than each contracting out the work for themselves. Coase's main explanation for this is that there are various transactions costs related to functioning in the open market that are eliminated when people create companies instead of subcontracting. For example, a certain person and his subcontractor would need to spend time bartering before agreeing on a price and this hassle is stricken through the organization of corporations, where many jobs and functions can be performed in-house.

The second reason, involving property rights, Coase published in a paper named "The Problem of Social Cost" (1960) in the Journal of Law and Economics while he was a faculty member at the University of Virginia. In this paper, Coase writes that it is unclear where the blame for externalities or negative consequences lie. He concludes that is important that the government clearly define property rights so that the question of who, in an economic scenario involving two or more parties, is the more harmed by a certain choice or action. In his words, "the problem is to avoid the more serious harm". Together with sufficient transaction costs, initial property rights matter for both equity and efficiency.

This leads to the famous "Coase Theorem" which is associated closely with Ronald Coase, who said that the theorem, taken from a few pages of his "The Problem of Social Cost" paper, was not about his work at all. Even though Coase said in his paper that property rights should be well defined, the Coase Theorem posits that if trade in an externality is possible and there are no transaction costs, then bargaining will lead to an efficient outcome regardless of the initial allocation of property (Wikipedia). In essence, involved parties don't have to consider how property rights are granted so long as they can negotiate and trade to produce a mutually advantageous outcome. His 1960 paper, however, argues that since transactions costs are rarely low enough to produce such an efficient outcome, the theorem is not applicable to economic reality.

Before reading about Mr. Coase in the New York Times last week, I knew nothing about him. I certainly did not know he was a Nobel Prize winner and such an esteemed luminary in the field of economics. Mr. Coase contributed a great deal and amount of research, and was arguably one of the greatest economists of the twentieth century. His inadvertent creation of the Coase Theorem has led to countless papers and research in the subfields of perfect competition, game theory, and the economics of government regulation. His work on transactions costs, social costs, and especially the nature of the firm, will be highly relevant to our class since we do talk about the economics of organizations. Ronald Coase died on September 2, 2013, at the age of 102.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)